Wendy McCulley was clear-eyed about her goal when she started her FUSE fellowship: to give students in Fresno as many options as possible after graduating from high school.

“My personal goal is to positively affect as many students as possible by helping to reveal to themselves their own voice, their options, and potential for growth,” she said.

This is no small feat in a community that faces big economic and racial equity issues. Fresno is one of the poorest communities in the country, and most students are struggling. At Fresno Unified School District, only one-third of students are performing at grade level. According to a report by the Fresno Bee, 31 percent of students in the district are proficient in English, while 22 percent are proficient in math.

Although those standardized test scores are actually improving, the gap between minority and white students is growing, according to the report. Of the English learners (non-native speakers), only 3 percent were proficient in English, and 6 percent in math. And 20 percent of African

American students are proficient in English, compared to 51 percent of white students. Similarly, 12 percent of African American students are proficient in math, compared with 42 percent of white students.

These statistics are what drove McCulley to stay close to her biggest stakeholders — the kids. During her fellowship, while working to close that gap through expanding relationships with higher education partners and career technical education options, she decided to volunteer at Williams Elementary School, mentoring 22 grade schoolers.

On the first day of the mentorship program, McCulley got a glimpse into the lives of the students who represented those statistics. Half of the students were African American, half Latino, and one white, and they sat in groups reflecting their race.

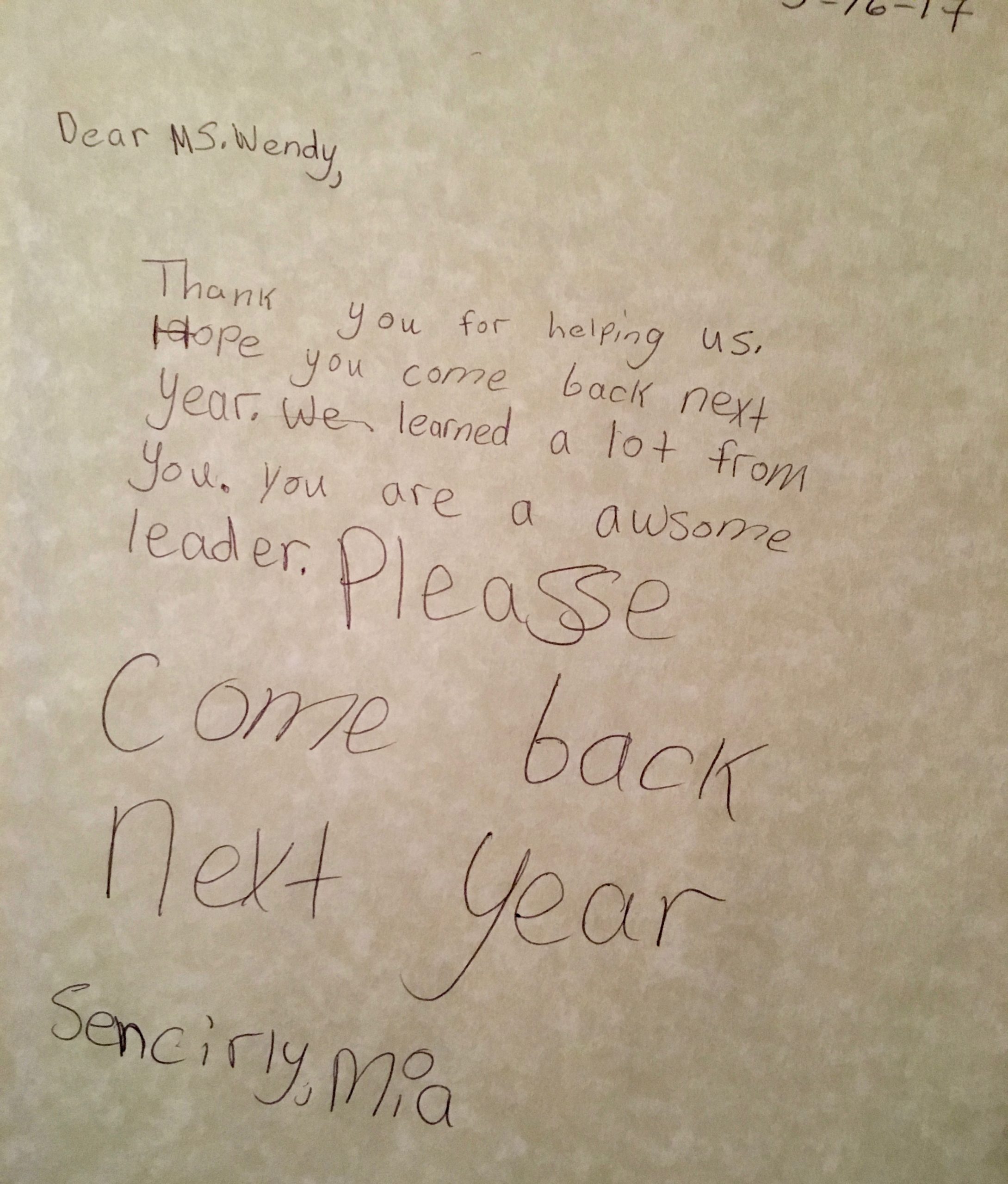

Most of them were having challenges with writing.

“Only a few kids could write a coherent sentence with correct punctuation, and even those kids had spelling issues,” McCulley said.

Student-Centered Lens

True to McCulley’s human-centered approach training, she decided to tailor the classes to what the students wanted to learn about, and build writing exercises around that.

So she asked her students: What do you want to get out of this program? She was rewarded with some poignant requests. They wanted to make new friends outside their existing social circles. They wanted to learn how to be ladies. They wanted to know what it’s like to go to college, to get outside of Fresno.

“I came from one of the poorest cities in the nation, so I could relate to their economic and racial hurdles,” McCulley said. “I wanted to interact with them as a caring adult who comes from the same background.”

She brought in an etiquette specialist. She had them do some improvisation activities to think about their choices, to get them to articulate why they’re making those choices. Simple exercises, like “Would you rather be an apple or orange, choose one, then explain why in writing.”

During one of McCulley’s exercises, she asked students to write something they liked about themselves as a way to get to understand themselves better.

One sixth-grade girl answered, “There’s nothing I like about myself.”

“Well, do you take care of your brothers and sisters”? McCulley asked the girl.

“Yes,” she said, and then wrote that down as an item on her list.

“She needs more affirmation,” McCulley said. “She was one of my better writers, and I told her to keep working on it. One day, she came up and hugged me, didn’t say a word.”

Other, more challenging questions she asked her students: Where do you want to live? What do you want to do when you grow up? How much money do you want to make? Do you want to help yourself, your family, or the world? Would you rather cure world hunger or stop crime? Then she asked them to come up with their own hard decisions to understand what it’s like to face these dualities.

“You will be judged by your choices as a young woman, and you need to understand why decision-making is important,” she said. “I pressed them to keep asking themselves ‘why.’ Don’t just take the first answer you think of, keep asking why.”

Based on their answers to what they wanted to be and where they wanted to live, she helped them figure out what kinds of courses they’d need to take, what college they could apply to, and if not college, then to name another goal. A baker, for example, would need to understand fractions. Lawyers need to be great writers and orators.

“They didn’t understand how those jobs correlated to what they were learning in school,” she said. “I saw a deeper need to help kids make that correlation between what they’re learning now and what they want to do in the future.”

Rather than take the students to workplace sites to show them a potential future career, or bringing in CEOs to talk to the students about how they got to their high-stature jobs, McCulley decided to bring in a recent Fresno Pacific graduate, someone the kids could relate to immediately, what she calls a “near peer experience.” To the students, the graduate looked like them and talked like them, and McCulley said they glommed onto her, and wouldn’t let her go.

Hearing from the college grad that day, the kids learned that it takes a lot of hard work and focus to get ahead. The graduate was the youngest in her family and the only one who went to college. She had to work three jobs, and she couldn’t go out with her friends, many of whom made different choices. She was home studying, saving money. But it was worth it, because she graduated and is on her way to getting her master’s degree.

“It’s a lot different when you see someone who grew up in your community and is making it work,” McCulley said.

Most importantly, all programs — academic or social emotional or both — need to be student-centered, based on the kids’ own interests. “They’ll show up, they’ll be more engaged and better able to weather difficult things,” she said. “Our kids are behind. Poverty is not a proxy for underachievement. Everything they touch needs to have an academic focus.”

Her biggest insight? “Kids are kids, no matter their backgrounds. And they’re all facing similar things, they’re all trying to find their way, and to be better,” she said. “I believe in the goodness of kids, and their highest potential and my mentees just reinforced this for me.”